The usual path to the Norman invasion runs through the invaded country and begins with Edward the Confessor–very nearly the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings. But you know what? We’re not taking that route. We’ll go through France and start with a French king named Louis the Stammerer.

Louis had reason to stammer. He’d secretly married a woman his father, Charles the Bald, hadn’t selected. (Bad prince. Daddy’s very displeased with you.) He and his contraband wife had two sons with boring names, then Charles the Bald had the marriage annulled and got Louis the Stammerer married to a woman he–that’s Charles the Bald–had chosen. They had one son, Charles, later known as Charles the Simple, who wasn’t born until after Louis the Stammerer died.

Have you ever wondered whether the introduction of family-based last names improved life? Using only the evidence we have on hand, I’d argue that it did.

Charles the Simple was considered the legitimate heir, since officially speaking an annulled marriage was rolled backwards until it had never happened, but it was a long time before C the S could do much more than eat, shit, and cry, which is another way of saying that even after he’d gotten himself born it took a while before he was any sort of political force. That left a blank spot and Wife Number One–the annulled wife–stepped into it: In 879 she maneuvered her sons onto the throne as joint rulers.

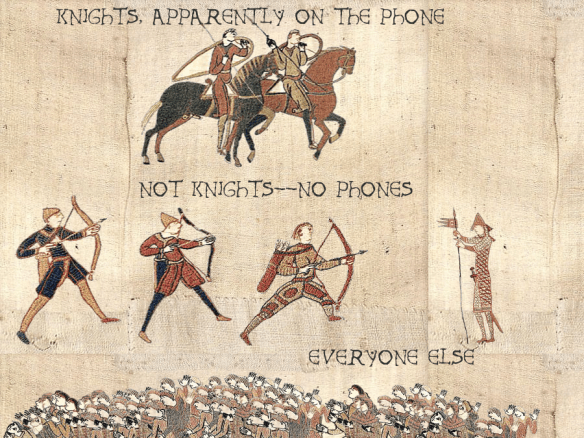

Want to make your own Bayeux Tapestry? You can do it online, thanks to Leonard A-L, Matieu, and Maria, whoever they are. Thanks, folks.

The brothers and the successors

The country the brothers were supposed to rule–that’s France, in case you’ve forgotten–had been beset by Viking raids for something like forty years and had been alternately fighting the raiders and buying them off. Neither approach worked for longer than forty minutes.

When the second of the co-kings died, France’s nobles installed Charles the Fat as king. We’re up to the year 884 now. Charles the Fat was the son of Louis the German, which isn’t particularly relevant but I can’t leave out anyone who has a good name.

C the F wrecked his reputation by not just paying the Vikings to end their siege of Paris (so far, so familiar) but also suggesting they go raid Burgundy instead. That did it for C the F and the nobles installed someone who was competent enough but had a dull name but had no family ties to previous kings. That problematic DNA meant he couldn’t be real a king, so to hell with competence, after ten years they got rid of him and installed Charles the Simple, who’d had the wisdom to emerge from an approved womb. He was nineteen.

To say Charles was simple wasn’t to say he was simple minded. It meant he was direct. Even so, the act he’s remembered for wasn’t his own idea but his nobles’: He made a treaty with a Viking chief who’d stayed in France after the siege of Paris and was using it as a base to conduct even more raids. The deal was that the Viking–Rollo the Walker–would recognize Charles as his king, convert to Christianity, marry Charles’s daughter, and stop with the raiding. In return, he was to become duke of the land now known as Normandy–from Norman: the Norsemen; the Vikings–and make it into a buffer state against future Viking raids.

Before formalizing the agreement, Rollo puffed up his fur, showed Charles how scary he was, and did some last-minute renegotiation, but he did put an end to the Viking raids on France and build a stable, Viking-inflected state in France.

From there Charles the Simple passes out of our story and we’ll follow Rollo for a few minutes, because he’s the three-times great-grandfather of William the Conqueror, the guy who invaded England.

Rollo

What do we know about Rollo? Not bloody much. He lived, he raided France, he became the Duke of Normandy and the three-times-great etc. of someone much better known. And he died. He was known as Rollo the Walker because–so rumor had it–he was too big to ride a horse. A trash-inflected web site that leans heavily toward explaining the history behind a marginally historical TV show tells me he was (or was said to be) 2 meters (that’s 6½ feet) tall and 140 kilos (that’s 308 pounds) in weight.

Well, other than weight what would he be 140 kilos in? Debt? Love? But don’t blame the trash-inflected site for that phrasing. It’s mine. I’d change it to something more graceful but I’d rather make fun of myself.

If you’re a fan of not knowing much about public figures, Rollo’s your guy. When archeologists opened the tomb of Rollo’s grandson and great-grandson, hoping to establish where Rollo himself came from (Norway? Denmark? Jenny Craig’s Weight Loss Clinic?), the bodies they found were some 200 years older than grandad/great-grandad himself.

Does it matter? To us, no. All we care about is that we’ve gotten the Normans settled into France, where they intermarried with the local population, integrated into the French power structure, and curled up in bed with a nice cup of hot chocolate.

The invasion

Okay, I’ll be honest with you: chocolate hadn’t made its way to Europe yet, and maybe that’s why William the Bastard–later known as William the Conqueror, which he probably preferred–got restless at being nothing more than the duke of Normandy, so that when Edward the Confessor died, having neglected to produce an heir, William decided to be a king in England as well. I mean, why not? Didn’t he have a marginally credible tale linking himself to Edward’s empty throne?

The problem was that another contestant lived closer and parked his hind end on it before William could, leaving an invasion as the only way to claim the fancy chair.

But invasions aren’t simple, so let’s go through the steps he had to take. First, he counted up the forces he could call on–his vassals and all their knights and assorted foot soldiers–and decided they weren’t enough, so both he and the vassals scooped up mercenaries, either paying them or promising them plunder in England. Wars were a business opportunity back then. Aren’t you glad we live in enlightened times?

The next step was to get everyone across the Channel, which is wet, even on a calm day.

Knowing we’d ask how he did that, English Heritage maintains a site telling us how to invade England. This isn’t a security risk. It’ll only help the modern invader who knows how to scroll technology back to what was available in 1066.

William needed enough ships to get 7,000 men across the channel. Or 5,000 to 8,000 if we go with a different source. Either way, it was more men than you’d want to invite home, even if they hadn’t been the kind of thugs you’d hesitate to let in the door.

Quick interruption: The combination of endemic sexism and the English language have, historically speaking, encouraged people to say “men” when they mean people, leading to no end of confusion, but this was a testosterone-soaked adventure and the men involved were biologically male. I can’t swear that there wasn’t a woman or two tucked into the invasion force, but they’d have been either add-ons or well hidden. (Yes, there is a history that’s only recently being uncovered of women going to war in disguise. That doesn’t mean one joined William, but I’d raise the possibility even if it’s for no better reason than to mess with our assumptions.)

Not all those men-of-the-male-persuasion would’ve been knights or even foot soldiers. To function, an army needed servants of various kinds. Nothing was automated or prepackaged. Everything that was done had to be done by hand. And it needed sailors–people who know how to keep the ships right side up.

In addition to all those people, William had to make room for the knights’ horses, because if you take away the horses, knights weren’t knights anymore. So let’s say 2,000 horses, And all those people and horses had to be fed and watered or they’d be no use to anyone. And the humans had to have alcohol or they’d get grumpy.

Or maybe they didn’t all have alcohol, but William did. He brought wine.

He also needed space for weapons, armor, and tempers. With all those mercenaries, you can figure that not everyone knew each other, liked each other, acted the same way, or spoke the same language, so we can pour a few regional and national rivalries into the human mix and stir in some alcohol.

I’m convinced they had alcohol.

By now we’re probably talking about 700 to 800 ships. One chronicler wrote that William had 3,000 ships, but we can take that as a poetic way of saying “a shipload of ships.” Even using the lower number, though, it really was a lot of ships and Normandy didn’t have enough, so they had to build them. You can see little figures in the Bayeux Tapestry cutting the trees to make the planks to construct the ships that lived in the house that Jack built.

Sorry. My mind skipped a groove there. The story has no Jack. That’s a children’s rhyme.

What happened next?

The fleet sailed. The fleet landed. The invaders took over the country. But this wasn’t a case of one population overrunning another, it’s is a tale of one elite displacing another, leaving the people on the bottom of the heap in place so they could keep working to support the people at the top. Without people at the bottom, the country wouldn’t be worth having. So all but a handful of Anglo-Saxon nobles lost their land and William’s most important followers gained it. Job done.

How well did William’s less important followers–the foot soldiers and mercenaries–do? The details of how spoils were divided is a bit hazy, but rank weighed heavily in the process. It’s a fair bet that the foot soldiers who lived through the fighting were better off than they would have been if they’d stayed home, but they wouldn’t have vaulted up the social ladder. To each according to his station.

So William’s key followers were paid off in land, but they weren’t given the power that in other situations would have gone along with it. The land was William’s to hand out, but the people he gave it to held it at his pleasure. In other words, he could also take it away. He’d created a highly centralized state, with himself–surprise, surprise–at the top.

*

Following the Norman invasion from the Norman perspective has made me realize that in most of the respectable histories–at least until recently, when the pattern’s started to break apart–tales of colonization and invasion are told from the invader’s perspective. New Zealand? Start with England and Captain Cook. The Americas? Africa? Asia? Start in Europe. Ireland? Start in England. The Norman invasion, though? This tale starts in England. That may be heavily flavored by my own limitations, because I don’t read French well enough to tackle anything above the level of a comic book, and they’re more work than they’re worth, but working through the process from this direction reminds me how much nationalism and other biases shape what we accept as history and how easy it is to forget there’s more than one way to tell the tale.

I think the tale is told from the English side because it wasn’t a French invasion and Normandy no longer holds England. It didn’t take very long for Normandy to become something that belonged to the kings of England, rather than England belonging to the Dukes of Normandy. Then a certain king lost Normandy altogether and the link was broken. The tale might start in France, but it ended just over a century later.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t disagree, but I do think it’s useful to shift our point of view when we’re exploring history. The same thing seems to happen with the Danelaw–the history’s generally follows the Anglo-Saxon chunk of England. I’m just the sort of contrarian who wants to know what’s going on in the area where no one’s turned on the lights.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is fascinating to look at it from that point of view, but I was thinking about why no one is particularly interested.

Will it surprise you to learn that I have at least five books in French that deal with medieval history? One’s about the Black Death, one’s about chivalry and one’s about the effect of the Middle Ages on modern France (not that modern, since I bought the book in 1980). Of the other two, one only starts with the Hundred Years War and the other, which starts with the Barbarians, has one sentence about William crushing the Saxons at Hastings. To be fair, it goes from the Barbarians to the Renaissance in 280 pages, so there’s not a lot of space to deal with William. It spends much more time on the Norman takeover of Sicily, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wait a minute: 1980 isn’t modern? Are you sure?

I’m impressed that you read French well enough to have five books in French on medieval history–and to have read them. But setting that (and 1980) aside, painful though that last decision may be, I expect the Battle of Hastings is a bit of a sideshow in French history, even though it’s the root cause of all those Anglo-French wars. Everything’s so intertwined, it’s amazing that anyone can write the history of a single country without detouring into the history of the entire planet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I studied French at university, which is why I bought most of the books in 1980. I was learning medieval French as an option and I wanted to know what was going on then.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And it set the path of a lifetime?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did the medieval option because I was interested in the tales of King Arthur, some of which were first written down in the twelfth century in France. It wasn’t a big leap to fourteenth-century England.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t entirely understand the pull the medieval period has on me, but it does hold a fascination. And sometimes it seems like anything I learn about the period is contradicted by something else I learn about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Annoying, isn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

And yet our own time hardly presents a consistent picture. It’s probably a good (and yes, annoying) reminder not to get sucked into the stereotypes we carry in our heads.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah Willy the Conk. Not a favourite up here in the harrowed north!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, I wouldn’t think so. I promise not to try to rehabilitate his reputation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great historical article!

Thanks a lot for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Luisa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re highly welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nora.

LikeLike

I was doing real good there until the end when I lost the thread. But hey I forgot to bring the needle so say lavie ! I know it is from a comic book. Getting back to Rollo you left out the part that he was like his latter day spiritual twin. Mongo. Yes they both rode bulls. There is an asterisk at the bottom of the Blazing Saddles credits that documents this little known bit of history. Have ever considered writing an encyclopedia entitled Anarchy Becomes History ? Come to think of it comparing your tale of Rollo and them Charles guys I see a lot of comparisons to #45 and that Borris fellow. The one from England not the continental ones…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s possible that you didn’t lose the thread but that I did. I’m not sure where the comparisons to our recent–and mercifully now deposed–alleged leaders–takes us. May they not conquer any nations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this capsule and the focus on names.

It pulls together things I have known in pieces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. It’s great to hear that.

LikeLike

Very interesting – because the Norman Invasion is one thing most U.S. school students have at least heard of, and some of us are nosey enough to want to know a bit more “deep background.”

Just as a side note : the research into women serving in war while disguised as men isn’t just recent. There are several documented cases of women who served during the American Civil War, including some that were only “discovered” when they sought to prove they were entitled to pensions. I think there were examples in the American Revolution too, though I’m not as familiar with the history of that war. And of course the women like Molly Pitcher who helped without any attempt to disguise their sex. There were a number of women who served as spies for both sides in the Civil War too, often taking advantage of being women to ingratiate themselves with sources on the other side.

Gotta love the evolution of “last names” too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And some were only discovered when they died–or were inconveniently wounded.

Oddly enough, I don’t remember reading about the Norman invasion in school. Maybe it got mentioned but it didn’t make enough of an impression to stay with me. I stumbled across it as, I’d guess, a teenager, outside of school, and thought, What????

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are not only insightful, but hilarious, too! Thank you for yet another great post!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for that. High praise indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great timing. My son and I were just discussing the Norman influence on Europe last night. (Yes, I know. It’s very odd.) Now we have a new perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(I was eavesdropping.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love English history. Fun read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know why, but it strikes me as so much more fun than American history. But maybe that’s because that was inflicted on me in school–with improper reverence, which absolutely squashed the life out of the poor thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I dunno. There’s just something about kings and queens of old(e).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most of the kings and queens don’t do much for me, although I’ll admit to having fun with the mayhem some of the early ones created. But there does seem to be something in the mix for all tastes. Like the best salad bowls.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have no problem with paying Vikings. Of course it is better to make them part of the family and get a cut.

In fact several of those “Germanic” tribes who “invaded” the Roman Empire a few centuries before Bastard Bill moved over (btw should we call it B-Day ?) were payed with land, incorporated.

Also the exchange of the ruling class was implemented in Northern Africa (was it the Goths ? Forgot, don’t want to look it up now, sorry). And yes, just as today, war was sometimes a business.

Don’t want to be too nit-picking, but you know that there is no “France” in the 9th century. Thankfully the poisonous snake of nationalism is still sleeping, it will awake roughly ten centuries later. Some of the guys with the funny nicknames (that are mostly inventions of later historiographers) are kings of the Westfrankenreich, the Western part of the Franconian, ahem, Empire. All successors of Karl, rightfully called “the Great”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No France? Goodness me, who did the English complain about?

To be marginally serious, though, I get tired of saying “the place that would later become” (it’s right up there with “the artist formerly known as” in the race for annoyingly awkward phrases), so I occasionally dodge behind the contemporary name and hope no one will care. Someone, inevitably, does. And, annoyingly, is right to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just call it “Holy Franconia” and I will bother you never again, in this respect, at least.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry, but that sounds too much like a line out of a Batman movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Blasphemy !

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love your writing style. Interesting stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Dan. It’s responses like that that keep me going.

LikeLiked by 1 person