When the Normans conquered England, they didn’t just bring their language–basically French, but you can call it Norman French if it makes you happy–they also brought the castle.

Not physically. Castles are heavy and prone to sea sickness. They brought the idea of the castle, and they set about building them in strategic spots as a way to keep control of their newly conquered land.

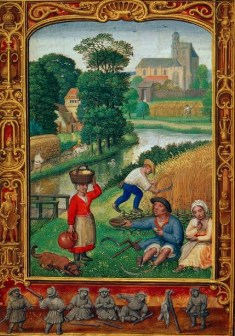

A rare relevant photo: Okehampton Castle, in Devon–or what’s left of it. In 1384, according to a nearby sign, it was owned by the Courtenays, who arrived with a household of 135 people: the family, of course, plus 61 servants, 41 esquires, 14 lawyers, 8 clergymen, and 3 damsels–young, unmarried women. I’m tempted to add six geese a-swimming and five gold rings but the sign doesn’t mention them so I won’t. When the family moved on, they left behind a small garrison, a gatekeeper, a constable, and a few men-at-arms.

The hell you say: didn’t the Anglo-Saxons have castles?

Nope. To defend the country from the Vikings, A couple of hundred years earlier, Alfred the Great–known in his own time as plain old King Alfred–had promoted the building of fortified towns, called burhs, and to attract settlers who’d defend them, he offered free plots of land inside the walls. I was about to write that it wasn’t a bad deal if you lived through an attack, but your chances of getting killed were probably just high if you were cutting hay. So, not a bad deal and I won’t add any qualifiers.

But burhs weren’t castles. They were closer to the fortified towns the Romans had built before they toddled off back to Rome (and the many other places they’d come from). In fact, some burhs used what was left of Roman fortifications as a starting point.

One theory holds that the Normans conquered England relatively easily because the country lacked castles. As Orderic Vitalis (monk; chronicler; son of an Anglo-Saxon mother and a Norman father; born in 1075, not long after the conquest) explained, “The fortifications that the Normans called castles were scarcely known in the English provinces, and so the English – in spite of their courage and love of fighting – could put up only a weak resistance to their enemies.”

So okay, castles were something new

The Normans built their first castles quickly, cheaply, and Ikea style. William the Conqueror–chief Norman and the new king–divided the land up among his newly be-lorded followers, and that land came well stocked with forests and dirt, which they used to assemble motte and bailey castles.

Motte and what? A motte was a big mound of earth (and inevitably, yes, some stone) and a bailey was the ditch and bank surrounding it. At the top was a wooden tower.

The problem with a wooden castle, though, was that if the Big Bad Anglo-Saxon Wolf came bearing a torch and followed by a bunch of pissed-off Anglo-Saxon wolflets, it would burn. What’s more, it would burn just as cheerily if instead of an Anglo-Saxon some invader set it alight. And if none of that happened, give it thirty or so years and the timbers would rot.

So William sent out a memo: rebuild the castles in stone.

More work, yes, but more durable, and as it happened Ikea had a kit for this too: the land held stone as well as wood and dirt. And lo, the lords followed the pictures on the instruction sheet and assembled more durable castles. Some kept the motte and bailey style; others went for a newer pattern that relied on massive stone walls to repel attackers.

But we’re not going to talk about architecture. I get bored easily. Let’s talk about . . .

. . . Why castles mattered

Have you ever wondered why an invading medieval army couldn’t just bypass the castles and rampage through the countryside while the lords and knights who were supposed to defend the land sat behind their walls eating, drinking, and acting lordly and knightly? Did the invading army really have to come to the door and challenge them to a fight?

As you may have figured out by now, military strategy isn’t one of my strengths, but here’s what I know: First, castles had a habit of getting themselves built where they could control a stretch of land: near roads, navigable rivers, ports, that sort of place. Helicopters hadn’t been invented, so the castles wouldn’t have been easy for an army to bypass.

Second, an invading army stomping around anywhere near a castle would’ve set the lines of communication buzzing. Word moved more slowly than it does today, but move it did, and it would’ve reached the castle and been a cue for the lord to gather up as many fighters as he could and get out into the field.

Third, if you were an invading army and the defending soldiers didn’t come out to meet you, you might have wanted to stop and dig them out while you knew where they were. Even if it did slow you down by a few weeks. Or in rarer cases, a few years.

And fourth, it was how things were done. How many of us think to question that?

But castles weren’t just forts. They were also administrative centers and homes to the lord, his family, his servants, his knights, and whatever other soldiers he had on hand–more in times of war; not so many in times of peace.

You notice that bass note thumping away there? His, his, his, his. Especially in the early part of the medieval period, this was a heavily masculine world, and a militarized one. The whole point of the aristocracy was to fight, but that job belonged only to the species.

Militarization was baked into the social structure: peasants toiled, priests and their churchly associates prayed, and lords fought. Warfare justified the aristocratic male’s existence and his dominance over the, ahem, lower orders. In Medieval Horizons, Ian Mortimer argues that not only were their lives centered around fighting, they–or many of them anyway–enjoyed the sheer brutality of it.

Why castles stopped mattering as much

Cannons took a lot of the fun out of castles. It’s true that cannons were big and heavy and not easy to lug around the countryside, and it’s also true that Ikea didn’t stock them, so they couldn’t be assembled on site, but from around 1400 on, they could wreck a castle wall. So they were well worth dragging around.

Forget waiting out a siege inside your thick stone walls. Warfare had changed.

Why were castles still used, then?

A castle was still good for what Ian Mortimer (Medieval Horizons; remember?) calls “regional control.” If you want to substitute “oppressing the peasantry,” be my guest. I wouldn’t sink to such a biased way of putting it but I can’t find an argument against you using it.

They also still served as residences, administrative centers (not unrelated to that oppressing business), and big honkin’ status symbols. The largest lords had multiple castles, and moved from one to the next, along with their households–lady, children, servants, hangers-on (secular and clerical)–taking their belongings with them, from beds to wall hangings to candlesticks and no doubt the candles as well. In times of peace, there would’ve been fewer soldiers and knights; in times of war, more. For an example, see the note under the photo. Breaking with all my traditions, the photo’s relevant to the post this week.

In the early century or three after the Norman invasion, traveling from castle to castle was about keeping that retinue fed. I can’t help thinking of them as a horde of locusts, needing to move on before they’d stripped the land clean. Move further into the middle ages, though, and that becomes less of an issue. One explanation I’ve seen is that the medieval warm period (800 – 1250 or 950 – 1250, depending on who you ask) came along and more food was grown. Another is that trade expanded. Between 1100 and 1300, more than 1,600 markets were established–something that can be traced because they needed permission. You can add a thousand fairs, so food could now follow the aristocrats and the aristocrats didn’t have to follow the food. And that’s as far as I can take that discussion. Sorry. I’m sure there’s more to be dug out.

As the castle’s military value decreased, the ratio of men to women evened out, and as the middle ages wore on, trekking from castle to castle became less of a thing. Lords tended to settle into a primary residence and make it more comfortable.