Regular service on this blog will resume soon–probably on Friday, although I make no promises. I’ve had a post in the queue, waiting for its moment in whatever faint sun Notes has to offer. In the meantime, after last Friday’s post about ICE activity and the Minneapolis resistance, I’ve been sent new bits of information, some from friends and some from news sources you may not have seen. I’d like to pass them on.

You will have figured this out if you’re awake and breathing, but I’ll say it anyway: Notes isn’t a newspaper. I can’t cover the situation with the thoroughness even a half-decent journalist could manage. But I also can’t sit on my couch eating popcorn and pretending none of this is happening. I grew up in the US and spent 40 long, cold years in Minneapolis, although I live in Britain now. What’s happening there is close to my heart and given the power the US wields in the world, it matters to all of us.

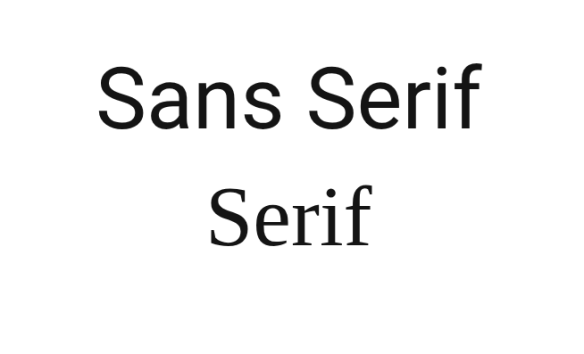

The usual irrelevant photo: Yes indeed, folks, it’s the moon and two trees. They’re in Cornwall, or at least the trees are. The moon is–or was–where moons usually are. None of it has nothing to do with anything.

News from friends

A friend writes that churches, community organizations, and businesses are collecting and delivering food, diapers, detergents, and other necessities to families hiding at home. They have an army of volunteers to collect and deliver. “My two faves,” she wrote, “are my dentist and . . . a sex toy store. Doulas have offered to help with delivery and postpartum care since women are afraid to go to the hospital. A vet said he’d take care of dogs by visiting homes for free. A couple guys with trucks offered to tow abandoned cars back to their owners’ homes. I just read now that the city will tow a car abandoned because of an ICE abduction for free. People are sitting in warm cars with clothes, food and burner phones to help people who just get thrown out into the freezing air after being detained.”

My goddaughter* writes, “Almost every place you go–shopping, churches, to work, doctor’s office, whatever–they have free whistles that are hanging by the doors for everyone to grab when you walk in because there is a good chance you’ll need one. Driving by [ICE agents] when they’re in the vehicles, they stare you down, challenging you with their eyes. People are giving out food, tear gas relief, effing GAS MASKS. I have a friend making entire kits for chemical irritant relief, free, funded via crowd sourcing. We are teaching each other new ways of protecting buildings with vulnerable people in them. At one of my jobs, I walk the perimeter hourly to scan for [ICE agents] camped out, looking for folks. We all have signs on locked doors indicating ICE is not permitted to enter.

“Yesterday they tear-gassed a PRESCHOOL looking for a 21-year-old teacher, who’s legal to be here. Neighbors surrounded the school to protect the kids, using their bodies as shields. They’re now using something called LRAD, which I’m learning causes permanent hearing damage, up to full deafness. They’re surrounding businesses they know cater to minority populations, just looking for anyone that looks like easy pickings. Bus stops and schools are DANGEROUS places to be right now. They’re targeting white people with cars full of groceries, because they assume they’re doing deliveries for scared neighbors. Those volunteers are advised to keep no records on their phones, paper only, and instructed to EAT THE PAPER if stopped to avoid giving away info on those families.

“We are all scared. But we can get through scared because we are on the right side of history. We love our neighbors here. We don’t back down. Considering they’re armed with guns and vests and aggression, and we are not, we’re doing ok. Not really, but we’re holding the line.”

It’s not all about ICE

A small Minneapolis charter school that’s focused on social justice was outed first by CNN, then by the New York Post, and after that by a paper further to the right than the Post, as the school Renee Good’s 6-year-old son attended. (Good was the first Minneapolis observer to be killed by ICE.) After that, the pile-on started. A Georgia congressman called for the school to be defunded.

“This institution radicalizes students and pushes a left-wing agenda that demonizes ICE agents,” he said. “The federal government should not subsidize anti-American education.”

A TikTok video said, “So, Renee Good was trained to fight federal agents through a Minneapolis charter school?!”

It got 100,000 views.

Social media went wild. Teachers got death threats and the school shut down its web presence and switched to online classes to keep students and teachers safe.

From social media and the news

St Paul’s mayor, Kaohly Her, who’s Hmong, writes that ICE is targeting the Karen community, a large ethnic group from southeast Asia.

“They are refugees and asylum seekers on the path to earning their green cards.

“ICE is now using a deceptive new tactic to detain them. Individuals receive ‘call-in’ letters instructing them to report to the Whipple Building [a federal building and the center of ICE activities in Minneapolis], warned that failure to appear could jeopardize their legal status. But when they do exactly what they’re told, they are detained on the spot — without an interview, without a case review.

“It’s a trap that puts people who came to this country seeking safety in an impossible position. These detainment tactics are cruel, deceptive, and deeply un-American.

“I recently visited the Karen community to pray together and to make clear that they are not alone — and that I will continue to stand with them.”

An article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune reports the people detained in the Whipple building–ICE’s all-purpose, overcrowded lockup–are being denied medical care, including diabetes and epilepsy medication, as well as products for their periods. Some report being given one sandwich a day and left to beg for water. Some are held in toilets, sometimes shackled or handcuffed, sometimes in mixed-sex groups, and packed in so tight that one person reported that they had to take turns to lie down. A woman reported that her wedding ring and some of her clothes were cut off. Citizens and legal immigrants are held separately from the undocumented, who conditions are worse.

Lawyers say it’s virtually impossible to get access to their clients.

And on Facebook, someone writes, On Facebook, someone writes, “One of the nuts things about organizing in the Twin Cities right now is that even the most long term organizers who’ve been here for decades can’t keep track of all the resistance that is going on. There are so many self-organized crews just doing work that in any conversation with someone from another neighborhood you might stumble over a whole collective of people resisting in ways you didn’t think of. There’s a crew of carpenters just going around fixing kicked-in doors. There are tow truck drivers taking cars of detained people away for free. People delivering food to families in hiding. So many local rapid response groups that the number is uncertain but somewhere between 80 and the low hundreds- especially when one considers that several immigrant communities have their own non-English rapid response networks usually uncounted in the main English-language directories. People standing watch outside daycares and schools.”

Two notable arrests

A legal Turkish immigrant who was his severely disabled son’s primary carer was picked up by ICE when he appeared at a regularly scheduled immigration hearing. His son’t condition deteriorated. The government refused to release him or let him communicate with his son.

When his son died, they refused to allow him to attend the funeral. He’s still in detention.

On a cheerier note, ICE picked up a Brazilian influencer who’d defended ICE, arguing that the people ICE had detained were “all crooks. The lot of them.”

Is it settling down?

After Alex Pretti’s killing caused an uproar, Trump made a few noises about dialing things down, but it doesn’t look like target groups (Asians; people who are brown- or black-skinned) are any safer. ICE has expanded its power to arrest people bothering to get a without warrant. As far as I can tell from the wording of the news articles I’ve seen, ICE granted that power to itself. A judge could overturn it, and may, but the order would then get bogged down in the courts until eventually Trump’s Supreme Court upheld ICE’s power to forgo warrants, and if the mood takes it, to turn spring to winter and wine to caustic soda.

The government’s offered to scale back the Minnesota operation if the state “cooperates.”

What does cooperate mean? With a bunch as chaotic as this, you can never be sure. I’ve seen one statement saying they want access to the prisons, presumably to deport people, but several say they want access to voter rolls, which raises the chilling (and not unlikely) prospect that they would use them to tip the November midterm elections in their favor. They’ve already asked 43 states for access and only 8 have allowed it. The ones that refused cite privacy concerns and the right of states to determine voter eligibility. The Justice Department has sued 23 for access.

The musicians fight back

I can offer you not one but three songs about the Minnesota resistance: Bruce Springsteen’s “Streets of Minneapolis,” Billy Bragg’s “City of Heroes,” and the Marsh Family’s “Minnesota,” an adaptation of the 1967 “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair)”; it keeps the original line about wearing flowers in your hair, which–sorry, guys–no sane Minnesotan would do in the winter and just isn’t a Minnesota kind of thing in the summer either. Never mind. The rest of it is a good fit.

____________

* If you’ve been around here for long, you will have stumbled over some mention of me being a Jewish atheist. So what am I doing with a (yes, Catholic) godkid? Religiously, I admit, it’s strange. It’s also been wonderful. My partner and I became joint godmothers, and it formalized our relationship with the family and let us know we were welcome to stay involved. I’m proud to quote her here and in awe of the person she’s grown up to be.