Set aside your stereotypes of Tudor England. It wasn’t all heretics going up in flames and virgin queens wearing so much clothing that how could they help being virginal?. Tudor England also developed a level of control freakery that reached deep into society.

Clothes

The Tudors inherited sumptuary laws–laws dictating who had the right to wear what–from Edwards III and IV, but the Tudors went wild with them. Only the royal family could wear purple or cloth-of-gold. Except for dukes and marquesses, who could wear a bit as long as it didn’t cost more than £5 a square yard. Earls and upward could wear sable. Barons and upward could wear cloth-of-silver or satin.

Other levels of society could wear silk shirts, gold or silver bordure (don’t ask; I’d guess trim but we don’t really need to know), crimson, blue velvet, scarlet, violet, and garments made “outside this realm.” The act listed the realm’s parts in case anyone wasn’t sure. Knights could wear this, lords’ sons could wear that.

Irrelevant photo: Meadowsweet, which was once used to flavor mead.

Moving down the social scale, hose that cost more than ten pence a yard could only be worn by a husbandman, shepherd, or laborer if he owned goods worth more than £10.

What’s £10 in modern money? Something along the lines of £5,000 in 1988 currency. Today it would be–um, more.

What happened to people who broke the rules? The important people would be fined. The husbandman, the shepherd, and the laborer would be put in the stocks for three days, and they’d lose the offending piece of clothing. Half the value would go to the king (this particular stature was Henry VIII’s) and the other half to the informant.

Actors, foreign ambassadors, and a few others got a free pass.

Servants, they weren’t supposed to wear blue, but blue became so common in servants’ livery that no gentleman would be seen in it. Which is enough to make a person wonder how much the laws were enforced.

All of that, though, was about men’s clothes. According to Jasper Ridley, whose book, The Tudor Age, I’m pulling this from, a woman who dressed “above her station” might be ridiculed, but she didn’t threaten the social order the way a man would and wasn’t legislated against.

Being part of a despised group has its occasional small benefits.

Hats, caps, and consumer protection

Along with the restrictions went some bits of consumer protection, dealing with cloth that shrank, overpriced cloth and caps, and a few other specifics. This led Parliament into some fairly intricate legislation limiting who could buy wool (middlemen pushed the price up), who could work as a weaver, and where weavers could set up their looms.

To protect the people who made hats and caps, though, Parliament limited imports: they had to be sold at the port where they landed and no one could buy more than twelve at a time. In 1571, a new act required anyone over the age of six to wear a woolen cap (made in England, thanks, with English wool) on Sundays and holy days unless they were traveling outside the town or village where they lived.

Nobles and men who owned land worth 20 marks a year could ignore that business with the woolen caps, and so could “maidens, ladies and gentlewomen.”

Wages & work

All this control stuff got serious when it came to work and pay. Two things led the government to at least try to keep a lid on wages: the plague (it hit England in the 14th century) and the gradual end of serfdom (also the 14th century). A series of pre-Tudor laws already capped wages and made it a criminal offense to pay more, although it was okay to pay less. When their turn came, the Tudors passed updated versions. The employer who paid over the maximum could be fined, and so could the person who accepted higher pay. Any unemployed artisan or workman who was offered work at those wages and refused it could be jailed until they agreed to take the job.

And the workman who quit before his contract was out could be both jailed and fined–unless, of course, his master gave his permission to quit or if a man joined the king’s service.

It wasn’t exactly serfdom, but it wasn’t what we’d call freedom either.

I assume this applied to women as well, but once writers decide that the word man includes women, as writers did so casually a thousand years ago when I was young, it’s hard to tell who anybody’s talking about at crucial moments.

Hours were also fixed, because “artificers and labourers retained to work and serve waste much part of the day and deserve not their wages.”

Whoever wrote that sentence wasted much part of a number of words (cut “retained to work and serve” and you haven’t changed the meaning) but probably didn’t dock his own pay.

Summer and winter hours were fixed, along with meal breaks.

Working people responded by refusing to enter into the usual work contracts, which ran for three months or a year. They became casual laborers, working from day to day, and could leave when they damn well pleased. That was outlawed in 1550, because that sort of people “live idly and at their pleasure, and flee and resort from place to place, whereof ensueth more inconveniences than can be at this present expressed and declared.”

More wasted words also ensued.

Under this new law, craftsmen–shoemakers, weavers, etc.–who hired unmarried workers without a contract were risking a fine and jail time. And journeymen had to accept a contract if it was offered, and if they couldn’t agree on a wage, a justice of the peace would set it.

All this seems to have been widely ignored, and under Elizabeth they tried again, but with wage rates that recognized inflation. Some other details changed, but they were reaching for the same thing: drive those lazy working people into the jobs that were going begging. I’ve heard contemporary politicians making pretty much the same noises, although the punishments have changed.

A few decades later, another act covered the same territory and complained that the earlier one wasn’t being enforced.

Pronunciation

If all that strikes you as too practical to count as control freakery, try this: Scholars disagreed about how a word should be pronounced in Greek. That was ancient Greek, mind you, so they couldn’t just hop on a cheap flight to Greece and ask around. The lack of any possible certainty left them free to argue, and the argument came with religious overtones (don’t ask). And since all religion was political, this mattered enough that it made perfect sense for the chancellor of Cambridge University to threaten any undergraduate using the pronunciation he disapproved of with a whipping.

I’m willing to bet the wrong pronunciation was whispered over many a pint of ale.

Warfare and sports

By the Tudor era, Europe had learned about explosives and figured out how to pour them into a tube so they could shoot projectiles–not just tubes the size of cannons but smaller weapons called arquebuses, which the English called hagbuts, and eventually pistols. But the longbow still had its uses. It was faster and it worked in the rain.

Even then, the English knew a lot about rain.

What’s that got to do with control freakery? England needed to keep its archers in practice, so a 1487 act, after deploring the decay of the country’s archery skill, set a maximum price for longbows. By 1504, though, they’d decided that the problem wasn’t the price of bows, it was the popularity of the crossbow. So a new law made it illegal for the average person to shoot a crossbow.

That must not’ve worked, because four more laws made it a crime for the average person to keep a crossbow at home or to carry one on the king’s highway. An exception was made for people living near the Scottish border, the sea, or several other areas that were considered lawless or vulnerable to attack. The small print said that if someone who owned land worth more than £100 a year saw the wrong person–basically, a poorer person–with a crossbow, they could confiscate it and have themselves a nice crossbow. Or the profit from its sale.

It was that kind of small print that made the Tudor control machine work.

Every man between 16 and 60 had to keep a longbow and arrows at home. From 7 on up, boys had to have a bow and arrows so they could learn to shoot.

In 1512, the government decided that the problem wasn’t just the crossbow, it was sports in general, so it limited tennis, bowls, and skittles to the upper classes. It also banned football, a game that could’ve passed for unarmed warfare, with no limit on the number of players and damned few rules. If someone had the ball, they (it could be a man or a woman) could be stopped by hitting, punching, tripping–pretty much anything short of murder.

Then in 1542 a new act noted that people were evading the older law by inventing games that hadn’t been banned yet (which is how shuffleboard got started) and it banned them, except at Christmas–and of course only for the lower classes. It added dice, cards, and quoits to the existing list.

Vagrants

Vagrants were an ongoing obsession of Tudor government, so let’s ask who became vagrants. Some were sailors or soldiers who’d been discharged. Some had been retainers of noblemen but had been let go when Henry VII limited the number of retainers a nobleman could keep. Some were cut loose when Henry VIII closed the monasteries. Some were laborers of one sort or another who refused to work for the pay and conditions that were offered. Some were university students. Some were children. Many were people who’d been pushed off their land by the enclosure movement, and I won’t go into that here. If you’re interested–and it’s worth knowing about–here’s a link. The enclosure movement comes in about a quarter of the way through the post.

Tudor laws also paint a picture of unauthorized physicians, solicitors (that’s one flavor of lawyer), palm readers, pardoners, actors, and players in unlawful games roaming the country and making trouble for the authorities. It’s enough to keep a sensible monarch awake at night.

Vagrants could be punished by whipping, by having their ears cut off, and by being returned to their home parishes. People who gave a vagrant food or shelter could be punished. Constables who refused to whip beggar children or cut off the ears of vagabonds could be punished, which hints that getting the laws enforced wasn’t a simple process, or necessarily a successful one.

After a certain number of non-lethal punishments, according to one law, a vagabond could be hanged. A different law would force a vagrant to work for any master who’d have them–for pay if possible, for food and drink if not. If the vagrant refused, the justice of peace could brand them and keep them as a slave and mistreat them in an assortment of specified ways.

Do you get a sense of the lawmakers settling on wilder and wilder solutions to a problem that wouldn’t go away?

In a fit of mercy and realism, the act proposing slavery was repealed in a few years and the country relaxed into mere ear-cutting and whipping–and taking away any children over the age of five and putting them to work without pay. Until a few decades later, when capital punishment was reintroduced on the third offense.

Starting in 1550, some provision began to be made for people who couldn’t work–the aged and impotent poor, they called them. They would be sent to abiding places and put to working doing whatever they could.

Welcome to the greatness of Tudor England. Your best bet is to hope you were born lucky.

Enforcement

Ridley calls the Tudor era despotism on the cheap. The government didn’t have hordes of civil servants–or what we’d call civil servants. What it had was a lot of enthusiastic but unpaid amateurs, and with the exception of Wales and parts of Northumberland, and of the occasional rebellion (Ridley counts eight) or riot, the country was pretty orderly. And the trains ran on time. None were scheduled for several centuries, so that was easy enough.

Local government was in the hands of sheriffs (and above them, lord lieutenants), mayors, justices of the peace, and on the lowest level, by constables, bailiffs, and officers of the watch. That’s not a lot if you think about keeping a country within the bounds of all those rules.

But the general public had to turn out and help catch any fugitive and had good reason to actually do it: If a felony was committed in the parish and the baddie (or some plausible substitute) wasn’t caught, every last householder was fined.

To keep criminals from escaping into Wales, ferries were banned from carrying anyone across the Severn at night. And the ferryman wasn’t to carry anyone unless he knew who he was and could report his name and address if he was asked. Which would’ve taxed the memory of anyone who couldn’t write.

In Northumberland, landlords could only rent land to people who found two men of property to vouch for them.

How well did any of this work? It’s hard to say. When you see various versions of the same law passed time after time, it’s a hint that the first ones didn’t work. So they probably didn’t stamp out sports, working people did continue to push for better pay, and vagrants, beggars, and vagabonds continued to roam the land, since the conditions that had produced the first batch continued to produce even more of them. And although servants weren’t supposed to wear the color blue, it was such a common part of their livery that no gentleman would be seen in it.

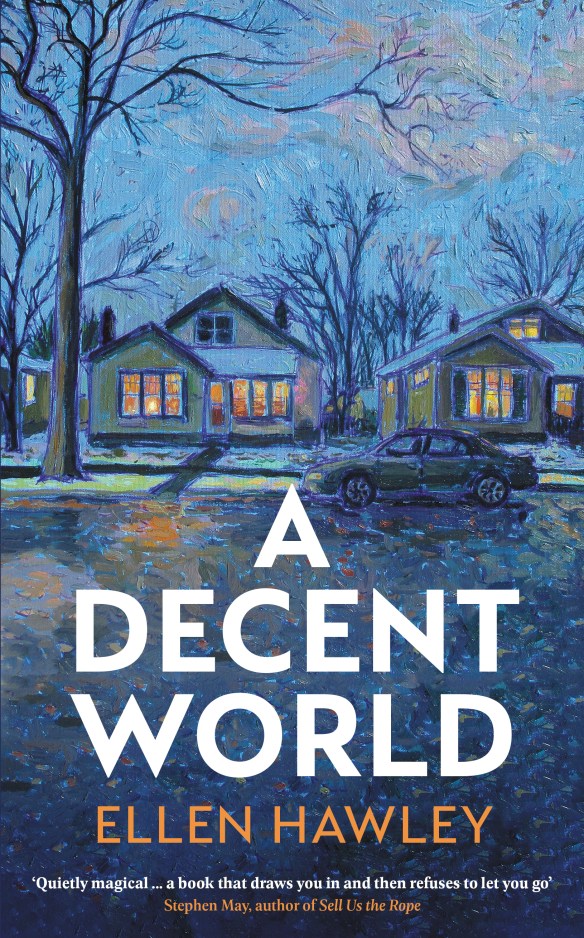

It’s time to announce a new novel.

It’s time to announce a new novel.