Britain has some of the world’s toughest gun regulations, and not only do the vast majority of people approve of that, 76% think they should be stricter. That’s from a sober poll taken in 2021, but Hawley’s Small and Unscientific Survey reports pretty much the same thing.

How did I conduct my survey? Effortlessly. I’m an American transplant, which leads British friends and acquaintances to ask periodically, “What is it with Americans and guns anyway? Are you people crazy?”

I’m paraphrasing heavily. Most people are too polite to ask if we’re crazy, but if you listen you can hear the question pulsing away, just below the surface. Basically, they’re both baffled and horrified by the US approach.

I should probably tell them that a majority of Americans (56%) also want stricter gun laws but haven’t managed to dominate the national conversation yet. That’s probably because they haven’t poured as much tightly focused money into political campaigns as the pro-gun lobby.

Am I being too cynical? In the age-old tradition of answering a question with a question, Is it possible to be too cynical these days?

Irrelevant photo: The Bude Canal

What are Britain’s gun laws?

For a long time, they were somewhere between minimal and nonexistent.

Way back when William and Mary crossed the channel in small boats, the price they paid to become Britain’s joint monarchs was accepting the 1689 Bill of Rights, which acknowledged that Parliament was the source of their power. It also guaranteed the right to bear arms–unless of course you were Catholic, who were the boogeymen of the moment. You were also excluded if you were some other (and barely imaginable) form of non-Protestant.

The relevant section says, “The subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions, and as allowed by law.”

That leaves some wiggle room: “suitable to their conditions”; “as allowed by law.” (The US second amendment is ambiguous as well. Maybe it’s something about weaponry.) So when in 1870 a new law required a license to carry a gun outside your home, it wasn’t a violation of W and M’s agreement, because this was a law. As far as I can tell from the wording, if all you wanted to do with your gun was set it on the kitchen table and gloat over it, you could skip the license.

In 1903, a new law required a license for any gun with a barrel shorter than 9 inches and banned ownership by anyone who was “drunken or insane.”

You could have a lot of fun poking holes in that. Could I get a license if I was sober all week but on the weekend I routinely got so drunk I fell in the horse trough? If I had a title and expensive clothes, would I still be considered a drunk (or a nut)?

Never mind. That was the law they passed. Nobody asks me to consult. It’s a mystery.

But let’s go back a couple of years, to 1901, as Historic UK does in its post on gun laws. Handguns were being widely advertised to cyclists, with no mention of licenses, although the ;need for them may have been so obvious to everyone involved that they didn’t need mentioning. Or enforcement may have been patchy.

Bikes were the hot new thing–the AI of the day–and everyone who had any claim to with-it-ness was rushing around on one. And maybe the cyclists felt vulnerable, out there in the countryside on their own, or maybe gun manufacturers saw an opportunity and manufactured a bit of fear to boost sales. To read the ads, every cyclist needed a handgun. They were advertised, variously, as the cyclist’s friend and the traveler’s friend. One ad said, “Fear no tramp.”

Before World War I (it started in 1914; you’re welcome), Britain had a quarter of a million licensed firearms and no way to count the unlicensed ones. Then the war turned Britain, along with a good part of the rest of the world, on its ear. One of its smaller side effects was that when it ended soldiers came home with pistols.

How’d they manage that? The army didn’t want them back? I consulted Lord Google on the subject, but I seem to have asked the wrong questions, because he went into a sulk and refused to tell me anything even vaguely relevant. But bring guns home they did, in large enough numbers that the government started losing sleep over it, because this was a turbulent time and the government had a lot of things to lose sleep over. For one thing, the Russian Revolution not only meant it had to share a planet with a revolutionary socialist government, it also kicked off a wave of revolutions in Europe that must’ve made it look, for a while, as if Britain would end up sharing the planet with multiple socialist governments.

Life was turbulent on British soil as well. Not all that long before the war, in 1911, a shootout in London involved two Latvian anarchists, a combination of the Metropolitan and City police departments, the Scots Guards, and Winston Churchill. The anarchists might not have been anarchists, though, but expropriators, carrying out robberies to support the Bolshevik movement. Either way, they were well armed and the police were armed only with some antique weapons they pulled together. Until the Scots Guards showed up, they were outgunned.

In “Forging a Peaceable Kingdom: War, Violence, and Fear of Brutalization in Post–First World War Britain,” Jon Lawrence argues that postwar Britain lived with a fear of violence from returned soldiers, the general public, and/or a government “brutalized” by the war. (The quotation marks are his. I’ll hand them back now that we’re ready to move on.)

The press was full of violent crime reports. When isn’t it, and when don’t we at least partially believe it’s a balanced picture of the world we live in? Still, the stories are part of the picture: fear was the air people breathed.

The soldiers returning from the war are also part of the picture: they came home to unemployment and its cousin, low pay. A wave of strikes swept the country, including a police strike and in 1919 a strike by soldiers–or if you want to put that another way, a mutiny. Some of that was violent and some wasn’t. All of it kept the government up at night.

In many cases, unemployment led to whites turning their anger on Blacks and immigrants, blaming them for taking their jobs. Familiar story, isn’t it? (Black, in this context, includes people from India. I only mention that to remind us all how fluid the categories that seem so fixed in our minds really are.)

Longstanding Black British communities were joined by a good number of sailors from both the military and the merchant fleets who were stranded in Britain when they were fired and their jobs filled by white sailors. Their hostels were a particular target for violence. Black and immigrant communities often defended themselves, leading to some full-on battles–and more lost governmental sleep.

For a fuller story on that, go to Staying Power: the History of Black People in Britain, by Peter Fryer. We’ll have to move on, because most of that is, again, a side issue to this topic. The point is that that was a turbulent period with a nervous government. In 1920, a new law allowed the police to deny a firearms permit to anyone “unfitted to be trusted with a firearm”–a loose category if there ever was one.

And after that?

In 1937–a different era but the midst of the Great Depression, so still a turbulent time–most fully automatic weapons were banned, then in 1967 shotguns had to be licensed. Applicants had to be “of good character, . . . show good reason for possessing a firearm, and the weapons had to be stored securely.”

In 1987, a man killed 16 people and himself, using two semi-automatic rifles and a handgun, and the government came under pressure to tighten the laws. In response, semi-automatic and pump-action rifles were banned, along with anything that fired explosive ammunition and a few other categories of weapons. Shotguns remained legal but had to be registered and stored securely.

After a 1996 shooting of 16 schoolkids and their teacher, in which the shooter used four legally owned pistols, a new law banned handguns above .22 caliber, and in 1997 .22s were outlawed.

In 2006, in response to a series of shootings, the manufacture, import, or sale of realistic imitation guns was banned, although it was still legal to own one. The logic there is that they look realistic enough to commit crimes with, so this isn’t exactly gun control; it’s more like toy control. The maximum sentence for carrying an imitation gun was doubled, and it became a crime to fire an air weapon outside. The minimum age for buying or owning an air weapon went from 17 to 18, and air weapons could now be sold only face to face.

In 2014, police were required to refuse or revoke a firearms license if the applicant or license holder had a record of domestic violence, drug and alcohol abuse, or mental illness, which implies that they’re expected to actually check.

And the result?

I know a few people in Britain who own rifles and shotguns that they hunt with. When they applied for licenses, they had to show that they had a secure place to store them, that they had a legitimate reason for owning a firearm, and that they were “of sound mind.” They had to pass police checks and inspections of their health, property, and criminal records. If any of them have moaned about it, I haven’t heard it.

As a way of looking at the impact, I thought I could find a nice, simple set of statistics comparing homicide rates in the US and UK, but nothing’s ever simple. If you use two different sites, one for each country, you end up comparing apples and motor scooters, but I did eventually find one that compares many countries’ murder rate per million people. In 2009 in the UK, it was 11.68; in the US, it was 44.45–four times higher. We’ll skip the intentional homicides, which aren’t the same as murders, along with the accidental deaths and the suicides. They might all be worth thinking about if we’re talking about the impact of gun ownership on death rates, but they’ll make my life more difficult and I don’t know how you feel about that but it won’t make me happy, so basically, screw it.

Another site I found compares mass shootings between 1998 and 2019. The UK’s had one. Twelve people died in it and one was injured. The US has had 101, making it the world’s leader in mass shootings. In the deadliest, sixty people died and more than eight hundred were injured. In the second deadliest, forty-nine died and fifty-eight were injured.

So is the US, with its permissive gun laws, a freer country than the UK? That’ll depend on how you define freedom, and that’s above my pay grade since I do this for free. Some people measure freedom by a country’s voting system, some by people’s sense of security and safety, and some by the right to carry a gun. I have yet to meet anyone in Britain who feels oppressed by the gun laws or measures their freedom by their access to weaponry. I’m sure someone out there does, but they’re a minority, and a small one.

What about the argument that access to weapons makes the little guy a more powerful political force? My observation is that the little guy struggles to be heard in both countries, but that guns and threats of violence in the US are allowing a minority–a sizable one but still a minority–to increase its power at the expense of their fellow citizens. That’s not a good fit for my definition of freedom.

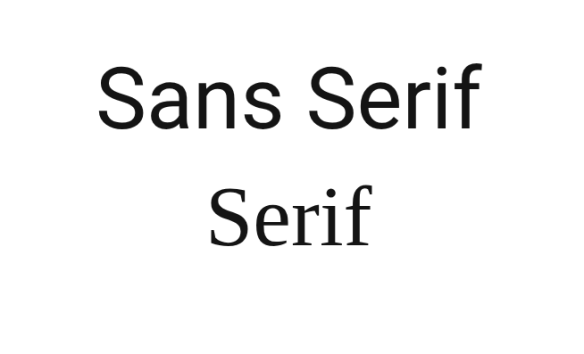

So that’s what we’re talking about, but still, when a rich and powerful nation orders its minions to abandon one typeface and use another, sane people everywhere rise up from their Crunchy Munchy Oatsies* and ask why the country has nothing better to do with its time.

So that’s what we’re talking about, but still, when a rich and powerful nation orders its minions to abandon one typeface and use another, sane people everywhere rise up from their Crunchy Munchy Oatsies* and ask why the country has nothing better to do with its time.