I know, I just wrote a post about red phone boxes and came down on the side of tradition, but really, folks, there’s a limit, and I believe a recent BBC TV series on Parliament has helped me locate it.

The series looks at everything from the building itself (which is falling apart) and the people who keep it running to the MPs and what they do and how they do it. How they do it is often in very arcane ways. How does one MP hand over some papers for a particular category of bill he’s introducing? He walks five steps, bows, walks five more steps, bows again, then walks the rest of the distance and hands over the papers. Makes me wonder what would happen if he didn’t bother bowing, or walked six steps. We played a game like that when I was a kid, Captain, May I? It involved giant steps and banana steps and going back to the starting line if you got it wrong.

The series is alternately fascinating, boring, and horrifying, and it wouldn’t be complete without a few Parliamentary traditions that predate the ox cart. And possibly the ox itself. I will, therefore, ignore the serious stuff and dive directly into the silly (in case I haven’t already done that with the MP and his banana steps). Because we all have enough serious stuff in our lives.

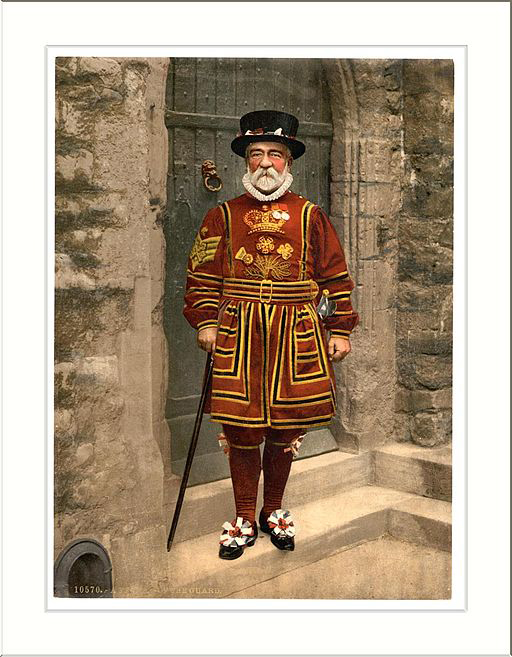

Before the Queen’s Speech (which gets capital letters, implying that it’s her only speech; for all I know, she maintains a regal silence the rest of the year), the Yeomen of the Guard walk through the basement pounding the corridor floors with fancy staffs, checking for barrels of gunpowder. It’s quite a sight, since these are the guys—and these days, I’m happy to say, at least one woman—who wear those memorable red uniforms.

But excuse me? Gunpowder? Barrels? Has anyone heard of drones? Or, I don’t know, intercontinental ballistic missiles? Semtex? There are so many ways to blow things up these days. And explosives aren’t the only danger a monarch faces. She could trip on the hem of her cape. She could fall victim to some prankster substituting one of my posts for the approved speech and there she’d be, with the wrong sheaf of papers in her hands and nothing to do but stop, doggedly read on, or ad lib. And ad libbing doesn’t look to me like one of the skills she’s practiced much.

She reads, by the way, from real paper. Yes, folks, paper. Talk about traditional! And while I’m interrupting myself, I can tell you that I just googled Semtex to make sure I wasn’t mistaking an explosive for a dishwashing liquid. That probably put me on somebody’s watch list. If I wasn’t there already.

But never mind all that. They tap the floors for gunpowder, not semtex and not rogue blog posts. It all dates back to Guy Fawkes and the gunpowder plot.

I want to be clear about this. I’m not recommending you blow up Parliament. Regardless of how you feel about monarchy or the British government or anything else, it would not help the political situation in any way. But there are certain ideas that shouldn’t be planted in people’s heads, and this is one of them. They made it all so picturesque. And I can’t help playing with scenarios. I’m a fiction writer, your honor. And a vegetarian.

No, I’m not sure that’s relevant either, but I mention it just in case—

[A late insertion here: When I first posted this, the paragraph above read, “I’m recommending” instead of “I’m not recommending.” Thanks to K.B., who wrote to say I really would end up on someone’s watch list. This is what happens when you recast a sentence too many times. Bits and pieces of the earlier versions get left in until it becomes meaningless, or means the opposite of what you meant it to mean, your honor.]

Let’s move on before they pass sentence. The Queen’s Speech also involves Black Rod. This is a guy dressed in clothes from another century—possibly another planet, but then who am I to judge?—and he runs around with, yes, a black rod. At the State Opening of Parliament, he’s “sent from the Lords Chamber to the Commons Chamber to summon MPs to hear the Queen’s Speech. Traditionally the door of the Commons is slammed in Black Rod’s face to symbolise the Commons independence.

“He then bangs three times on the door with the rod. The door to the Commons Chamber is then opened and all MPs—talking loudly—follow Black Rod back to the Lords to hear the Queen’s Speech.”

That, by the way, is from Parliament’s own web site. You can tell it’s not mine by the British spelling of symbolise. Not to mention the quotation marks and the straight-faced tone.

This bit of symbolism dates back to the 1600s, when Charles I tried and failed to arrest five MPs, which Parliament considers to mark the autonomy of the Commons from the crown. Slamming the door in Black Rod’s face is like checking for gunpowder. It meant something once and they’ve been re-enacting it ever since.

So as far as I’m concerned, that’s where the far edge of tradition lies. I am, honestly, fascinated that the more, ummm, picturesque traditions continue on. I imagine that with each century they take on a more ceremonial and less meaningful tone, but no one can get rid of them. Maybe no one wants to. Maybe it’s only rude outsiders who see it all as a touch—shall we say bizarre and unnecessary? I don’t want to sound like I think the U.S. has it all figured out. We’re at least as crazy as the next country. But in other and (to me, at least) less picturesque ways.