Recently, a teachers’ conference objected to the government’s drive to teach British values in the schools, saying it was becoming “the source of wider conflict rather than a means of resolving it.” (“Teachers urged to ‘disengage’ from promotion of British values”)

I’ve been hearing about British values since I first came to this country, and I always wonder what they are. Standing in orderly lines? Forming brass bands? Not using sunscreen on the beach, even though you’re light-skinned and have already turned an alarming shade of pink? It’s a heavy responsibility, settling on a handful of characteristics to sum up an entire nation.

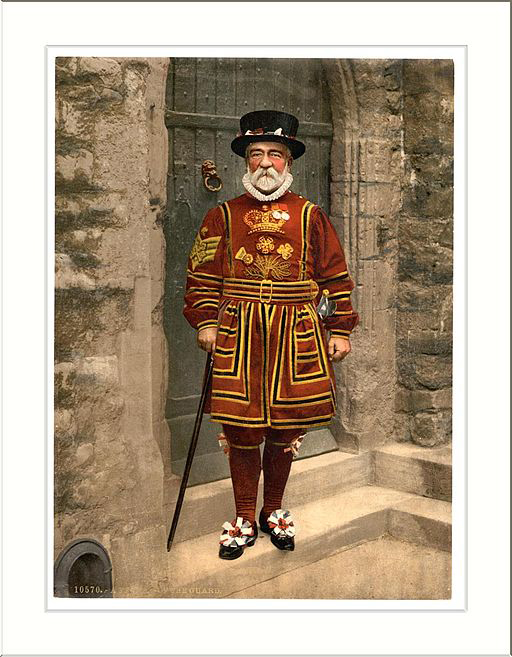

Irrelevant photo: The coast on the same hazy day as the last waves-in-the-haze picture I posted. The haze was caused by a sandstorm in the Sahara.

What did the Department for (not of, thank you very much*) Education decide were the ultimate British values when they pushed the nation’s protesting teachers under the wheels of this particular train? “Democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance for those of different faiths and beliefs.” (“Schools ‘must actively promote British values’ – DfE”)

Don’t you just love a politician who can say stuff like that with a straight face? Because, of course, no other country in this battered old world can lay claim to those ideals. If you’re startled awake some night and hear that set of values marching down the street behind a brass band, you’ll know right away what country you woke up in.

Any discussion of British values is complicated by a central reality of Britain, which is that the country’s a mash-up of four (or five, if you’re a Cornish nationalist) nations**, and the people most likely to call themselves British seem to be those of us who aren’t English, Scottish, Northern Irish, or Welsh. Or Cornish. In other words, those of us who came from someplace else. Those of us whose children the Department for Education is worried about Britishizing.

As far as I can tell, summing up either a country or its values is a messy business, whatever country you pick. When I still lived in the U.S., I taught briefly in a community college, and we’d read an essay by an immigrant that made a passing reference to, if I remember right, “being more like an American.”

“What,” I asked, on the spur of the moment, “does it mean when you say someone’s like an American?”

It wasn’t a question I had an answer for, and as it turned out no one else did either. The class broke into small groups, and a couple of them set about finding some essential trait that would separate the Americans from the non-Americans, but pretty much everything people suggested fell apart. Being born in the country? Nope. You could still become a citizen, and a citizen was an American. Being a citizen, then? Well, legally, yes, but some non-citizens are as culturally American (whatever that means) as any citizen. One small group, pushed, I think, by a single enthusiast, decided that speaking English was a dividing line, but the other groups didn’t jump in to endorse that. Personally, I’m all for speaking the language of a country you live in (British and American expats in non-English-speaking countries, are you taking notes?), but not every immigrant can learn a new language. My great-grandmother never did, even though the price she paid was not being able to talk freely with her grandchildren. It wasn’t lack of motivation. She wasn’t young when she immigrated and she couldn’t make the adjustment. Maybe she wasn’t good with languages. Maybe she was terrified. I don’t know.

No one, including me, thought to mention that other countries speak English and it hasn’t made them particularly American. In fact, some countries—mentioning no names—think they speak it better than we do. And then there are the Puerto Ricans. They’re U.S. citizens by birth. If some of them speak only Spanish, either by choice or because it’s their only language, are they any less American?

I won’t go on. We couldn’t say what being American meant, although we all thought we knew.

So, British values? Sorry, folks, but I’m not hopeful. I will, however, have a hell of a good time listening to the debate as it staggers on.

—————–

*My spies tell me it used to be the Department of Education, but the name was changed at some point. I’m sure the education system is better because of it.

**I owe the insight about the U.K. being a country of four (or five) nations to my writers group. The United Kingdom looks a whole lot more united from the other side of the Atlantic. In fact, Scotland came very close to leaving in 2014. Somebody tell me: Did that get any coverage in the U.S.?